Civil Liberties Are Being Trampled by Exploiting "Insurrection" Fears. Congress's 1/6 Committee May Be the Worst Abuse Yet.

Following the 9/11 script, objections to government overreach in the name of 1/6 are demonized as sympathy for terrorists. But government abuses pose the greater threat.

When a population is placed in a state of sufficiently grave fear and anger regarding a perceived threat, concerns about the constitutionality, legality and morality of measures adopted in the name of punishing the enemy typically disappear. The first priority, indeed the sole priority, is to crush the threat. Questions about the legality of actions ostensibly undertaken against the guilty parties are brushed aside as trivial annoyances at best, or, worse, castigated as efforts to sympathize with and protect those responsible for the danger. When a population is subsumed with pulsating fear and rage, there is little patience for seemingly abstract quibbles about legality or ethics. The craving for punishment, for vengeance, for protection, is visceral and thus easily drowns out cerebral or rational impediments to satiating those primal impulses.

The aftermath of the 9/11 attack provided a vivid illustration of that dynamic. The consensus view, which formed immediately, was that anything and everything possible should be done to crush the terrorists who — directly or indirectly — were responsible for that traumatic attack. The few dissenters who attempted to raise doubts about the legality or morality of proposed responses were easily dismissed and marginalized, when not ignored entirely. Typically, they were vilified with the accusation that their constitutional and legal objections were frauds: mere pretexts to conceal their sympathy and even support for the terrorists. It took at least a year or two after that attack for there to be any space for questions about the legality, constitutionality, and morality of the U.S. response to 9/11 to be entertained at all.

For many liberals and Democrats in the U.S., 1/6 is the equivalent of 9/11. One need not speculate about that. Many have said this explicitly. Some prominent Democrats in politics and media have even insisted that 1/6 was worse than 9/11.

Joe Biden's speechwriters, when preparing his script for his April address to the Joint Session of Congress, called the three-hour riot “the worst attack on our democracy since the Civil War.” Liberal icon Rep. Liz Cheney (R-WY), whose father's legacy was cemented by years of casting 9/11 as the most barbaric attack ever seen, now serves as Vice Chair of the 1/6 Committee; in that role, she proclaimed that the forces behind 1/6 represent “a threat America has never seen before.” The enabling resolution that created the Select Committee calls 1/6 “one of the darkest days of our democracy.” USA Today’s editor David Mastio published an op-ed whose sole point was a defense of the hysterical thesis from MSNBC analysts that 1/6 is at least as bad as 9/11 if not worse. S.V. Date, the White House correspondent for America's most nakedly partisan "news” outlet, The Huffington Post, published a series of tweets arguing that 1/6 was worse than 9/11 and that those behind it are more dangerous than Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda ever were.

And ever since the pro-Trump crowd was dispersed at the Capitol after a few hours of protests and riots, the same repressive climate that arose after 9/11 has prevailed. Mainstream political and media sectors instantly consecrated the narrative, fully endorsed by the U.S. security state, that the United States was attacked on 1/6 by domestic terrorists bent on insurrection and a coup. They also claimed in unison that the ideology driving those right-wing domestic terrorists now poses the single most dangerous threat to the American homeland, a claim which the intelligence community was making even before 1/6 to argue for a new War on Terror (just as neocons wanted to invade and engineer regime change in Iraq prior to 9/11 and then exploited 9/11 to achieve that long-held goal).

With those extremist and alarming premises fully implanted, there has been little tolerance for questions about whether proposed responses for dealing with the 1/6 “domestic terrorists" and their incomparably dangerous ideology are excessive, illegal, unethical, or unconstitutional. Even before Joe Biden was inaugurated, his senior advisers made clear that one of their top priorities was to enact a bill from Rep. Adam Schiff (D-CA) — now a member of the Select Committee on 1/6 — to import the first War on Terror onto domestic soil. Even without enactment of a new law, there is no doubt that a second War on Terror, this one domestic, has begun and is growing, all in the name of the 1/6 "Insurrection" and with little dissent or even public debate.

Following the post-9/11 script, anyone voicing such concerns about responses to 1/6 is reflexively accused of minimizing the gravity of the Capitol riot and, worse, of harboring sympathy for the plotters and their insurrectionary cause. Questions or doubts about the proportionality or legality of government actions in the name of 1/6 are depicted as insincere, proof that those voicing such doubts are acting not in defense of constitutional or legal principles but out of clandestine camaraderie with the right-wing domestic terrorists and their evil cause.

When it comes to 1/6 and those who were at the Capitol, there is no middle ground. That playbook is not new. "Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists" was the rigidly binary choice which President George W. Bush presented to Americans and the world when addressing Congress shortly after the 9/11 attack. With that framework in place, anything short of unquestioning support for the Bush/Cheney administration and all of its policies was, by definition, tantamount to providing aid and comfort to the terrorists and their allies. There was no middle ground, no third option, no such thing as ambivalence or reluctance: all of that uncertainty or doubt, insisted the new war president, was to be understood as standing with the terrorists.

The coercive and dissent-squashing power of that binary equation has proven irresistible ever since, spanning myriad political positions and cultural issues. Dr. Ibram X. Kendi's insistence that one either fully embrace what he regards as the program of "anti-racism” or be guilty by definition of supporting racism — that there is no middle ground, no space for neutrality, no room for ambivalence about any of the dogmatic planks — perfectly tracks this manipulative formula. As Dr. Kendi described the binary he seeks to impose: “what I'm trying to do with my work is to really get Americans to eliminate the concept of 'not racist’ from their vocabulary, and realize we're either being racist or anti-racist." Eight months after the 1/6 riot — despite the fact that the only people who died that day were Trump supporters and not anyone they killed — that same binary framework shapes our discourse, with a clear message delivered by those purporting to crush an insurrection and confront domestic terrorism. You're either with us, or with the 1/6 terrorists.

What makes this ongoing prohibition of dissent or even doubt so remarkable is that so many of the responses to 1/6 are precisely the legal and judicial policies that liberals have spent decades denouncing. Indeed, many of the defining post-1/6 policies are identical to those now retrospectively viewed as abusive and excessive, if not unconstitutional, when invoked as part of the first War on Terror. We are thus confronted with the surreal dynamic that policies long castigated in American liberalism — whether used generally in the criminal justice system or specifically in the name of avenging 9/11 and defeating Islamic extremism — are now off-limits from scrutiny or critique when employed in the name of avenging 1/6 and crushing the dangerous domestic ideology that fostered it.

Almost immediately after the Capitol riot, some of the most influential Democratic lawmakers — Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and House Homeland Security Committee Chair Bennie Thompson (D-MS), who also now chairs the Select 1/6 Committee — demanded that any participants in the protest be placed on the no-fly list, long regarded as one of the most extreme civil liberties assaults from the first War on Terror. And at least some of the 1/6 protesters have been placed on that list: American citizens, convicted of no crime, prohibited from boarding commercial airplanes based on a vague and unproven assessment, from unseen and unaccountable security state bureaucrats, that they are too dangerous to fly. I reported extensively on the horrors and abuses of the no-fly list as part of the first War on Terror and do not recall a single liberal speaking in defense of that tactic. Yet now that this same brute instrument is being used against Trump supporters, there has not, to my knowledge, been a single prominent liberal raising objections to the resurrection of the no-fly list for American citizens who have been convicted of no crime.

With more than 600 people now charged in connection with the events of 1/6, not one person has been charged with conspiracy to overthrow the government, incite insurrection, conspiracy to commit murder or kidnapping of public officials, or any of the other fantastical claims that rained down on them from media narratives. No one has been charged with treason or sedition. Perhaps that is because, as Reuters reported in August, “the FBI has found scant evidence that the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol was the result of an organized plot to overturn the presidential election result.” Yet these defendants are being treated as if they were guilty of these grave crimes of which nobody has been formally accused, with the exact type of prosecutorial and judicial overreach that criminal defense lawyers and justice reform advocates have long railed against.

Dozens of the 1/6 defendants have been denied bail, thus being imprisoned for months without having been found guilty of anything. Many are being held in unusually harsh and bizarrely cruel conditions, causing a federal judge on Wednesday to hold “the warden of the D.C. jail and director of the D.C. Department of Corrections in contempt of court,” and then calling on the Justice Department "to investigate whether the jail is violating the civil rights of dozens of detained Jan. 6 defendants.” Some of the pre-trial prison protocols have been so punitive that even Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) — who calls the 1/6 protesters "domestic terrorists” — denounced their treatment as abusive: “Solitary confinement is a form of punishment that is cruel and psychologically damaging,” Warren said, adding: “And we’re talking about people who haven’t been convicted of anything yet.” Warren also said she is "worried that law enforcement officials are deploying it to 'punish' the Jan. 6 defendants or to 'break them so that they will cooperate.”

The few 1/6 defendants who have thus far been sentenced after pleading guilty have been subjected to exceptionally punitive sentences, the kind liberal criminal justice reform advocates have been rightly denouncing for years. Several convicted of nothing more than trivial misdemeanors are being sentenced to real prison time; last week, Michigan's Robert Reeder pled guilty to “one count of parading, demonstrating or picketing in a Capitol building” yet received a jail term of 3 months, with the judge admitting that the motive was to “send a signal to the other participants in that riot… that they can expect to receive jail time.”

Meanwhile, long-controversial SWAT teams are being routinely deployed to arrest 1/6 suspects in their homes, and long-time liberal activists denouncing these tactics have suddenly decided they are appropriate for these Trump supporters. That prosecutors are notoriously overzealous in their demands for harsh prison time is a staple of liberal discourse, but now, an Obama-appointed judge has repeatedly doled out sentences to 1/6 defendants that are harsher and longer than those requested by DOJ prosecutors, to the applause of liberals. In sum, these defendants are subjected to one of the grossest violations of due process: they are being treated as if they are guilty of crimes — treason, sedition, insurrection, attempted murder, and kidnapping — which not even the DOJ has accused them of committing. And the fundamental precept of any healthy justice system — namely, punishment for citizens is merited only once they have been found guilty of crimes in a court of law — has been completely discarded.

Serious questions about FBI involvement in the 1/6 events linger. For months, Americans were subjected to a frightening media narrative that far-right groups had plotted to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, only for proof to emerge that at least half of the conspirators, including its leaders, were working for or at the behest of the FBI. Regarding 1/6, the evidence has been clear for months, though largely confined to right-wing outlets, that the FBI had its tentacles in the three groups it claims were most responsible for the 1/6 protest: the Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, and the Three Percenters. Yet last month, The New York Times acknowledged that the FBI was directly communicating with one of its informants present at the Capitol, a member of the Proud Boys, while the riot unfolded, meaning “federal law enforcement had a far greater visibility into the assault on the Capitol, even as it was taking place, than was previously known.” All of this suggests that to the extent 1/6 had any advanced centralized planning, it was far closer to an FBI-induced plot than a centrally organized right-wing insurrection.

Despite this mountain of abuses, it is exceedingly rare to find anyone outside of conservative media and MAGA politics raising objections to any of this (which is what made Sen. Warren's denunciation of their pre-trial prison conditions so notable). The reason is obvious: just as was true in the aftermath of 9/11, people are petrified to express any dissent or even question what is being done to the alleged domestic terrorists for fear of standing accused of sympathizing with them and their ideology, an accusation that can be career-ending for many.

Many of the 1/6 defendants are impoverished and cannot afford lawyers, yet private-sector law firms who have active pro bono programs will not touch anyone or anything having to do with 1/6, while the ACLU is now little more than an arm of the Democratic Party and thus displays almost no interest in these systemic civil liberties assaults. And for many liberals — the ones who are barely able to contain their glee at watching people lose their jobs in the middle of a pandemic due to vaccine-hesitancy or who do not hide their joy that the unarmed Ashli Babbitt got what she deserved — their political adversaries these days are not just political adversaries but criminals and even terrorists, rendering no punishment too harsh or severe. For them, cruelty is not just acceptable; the cruelty is the point.

The Unconstitutionality of the 1/6 Committee

Civil liberties abuses of this type are common when the U.S. security state scares enough people into believing that the threat they face is so acute that normal constitutional safeguards must be disregarded. What is most definitely not common, and is arguably the greatest 1/6-related civil liberties abuse of them all, is the House of Representatives Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol.

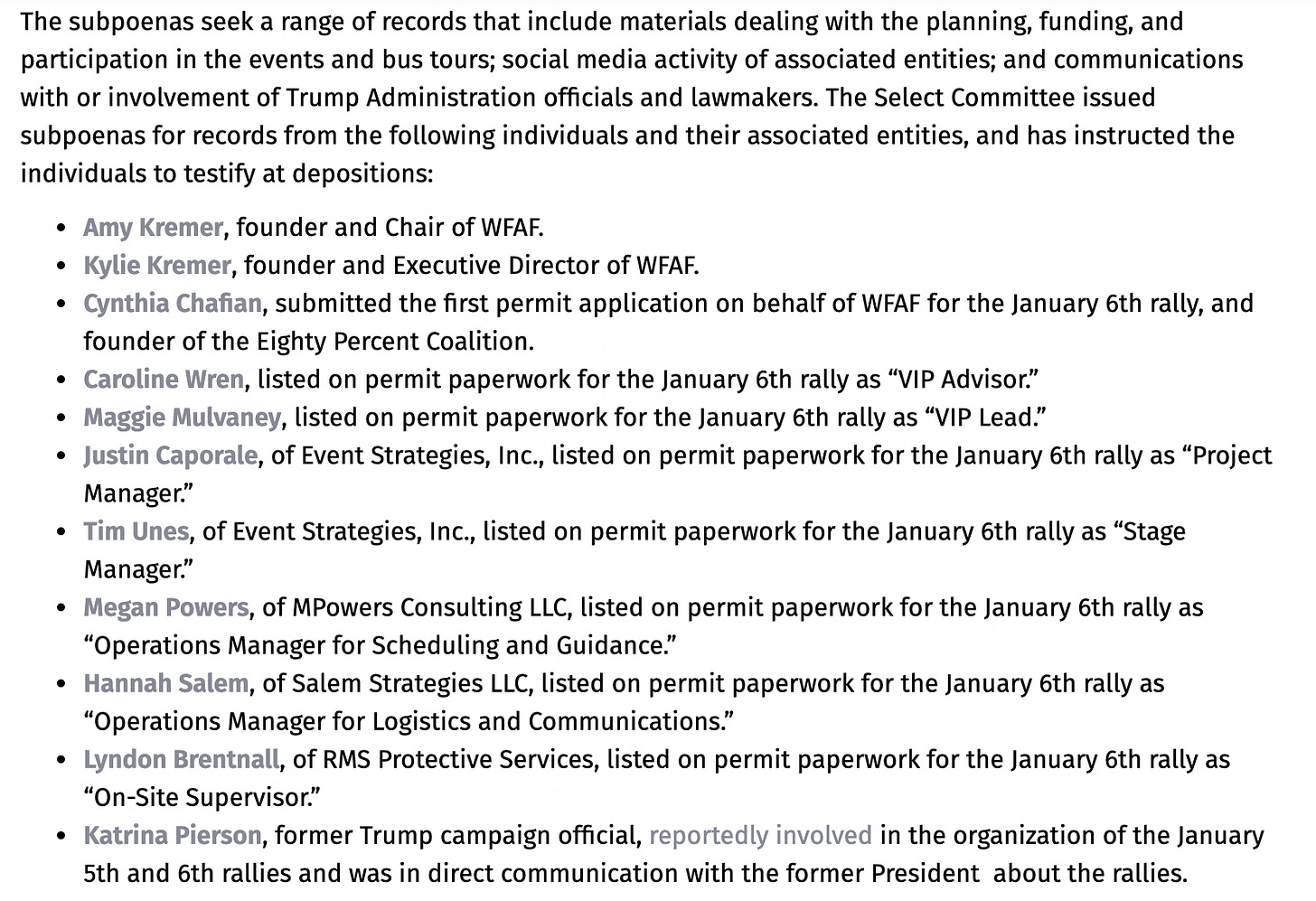

To say that the investigative acts of the 1/6 Committee are radical is a wild understatement. Along with serving subpoenas on four former Trump officials, they have also served subpoenas on eleven private citizens: people selected for interrogation precisely because they exercised their Constitutional right of free assembly by applying for and receiving a permit to hold a protest on January 6 opposing certification of the 2020 election.

When the Select 1/6 Committee recently boasted of these subpoenas in its press release, it made clear what methodology it used for selecting who it was targeting: “The committee used permit paperwork for the Jan. 6 rally to identify other individuals involved in organizing.” In other words, any citizen whose name appeared on permit applications to protest was targeted for that reason alone. The committee's stated goal is “to collect information from them and their associated entities on the planning, organization, and funding of those events": to haul citizens before Congress to interrogate them on their constitutionally protected right to assemble and protest and probe their political beliefs and associations:

Even worse are the so-called "preservation notices" which the committee secretly issued to dozens if not hundreds of telecoms, email and cell phone providers, and other social media platforms (including Twitter and Parler), ordering those companies to retain extremely invasive data regarding the communications and physical activities of more than 100 citizens, with the obvious intent to allow the committee to subpoena those documents. The communications and physical movement data sought by the committee begins in April, 2020 — nine months before the 1/6 riot. The committee refuses to make public the list of individuals it is targeting with these sweeping third-party subpoenas, but on the list are what CNN calls "many members of Congress," along with dozens of private citizens involved in obtaining the permit to protest and then promoting and planning the gathering on social media.

What makes these secret notices especially pernicious is that the committee requested that these companies not notify their customers that the committee has demanded the preservation of their data. The committee knows it lacks the power to impose a "gag order” on these companies to prevent them from notifying their users that they received the precursor to a subpoena: a power the FBI in conjunction with courts does have. So they are relying instead on "voluntary compliance" with the gag order request, accompanied by the thuggish threat that any companies refusing to voluntarily comply risk the public relations harm of appearing to be obstructing the committee's investigation and, worse, protecting the 1/6 “insurrectionists.”

Worse still, the committee in its preservation notices to these communications companies requested that “you do not disable, suspend, lock, cancel, or interrupt service to these subscribers or accounts solely due to this request,” and that they should first contact the committee “if you are not able or willing to respond to this request without alerting the subscribers." The motive here is obvious: if any of these companies risk the PR hit by refusing to conceal from their customers the fact that Congress is seeking to obtain their private data, they are instructed to contact the committee instead, so that the committee can withdraw the request. That way, none of the customers will ever be aware that the committee targeted their private data and will thus never be able to challenge the legality of the committee's acts in a court of law.

In other words, even the committee knows that its power to seek this information about private citizens lacks any convincing legal justification and, for that reason, wants to ensure that nobody has the ability to seek a judicial ruling on the legality of their actions. All of these behaviors raise serious civil liberties concerns, so much so that even left-liberal legal scholars and at least one civil liberties group (obviously not the ACLU) — petrified until now of creating any appearance that they are defending 1/6 protesters by objecting to civil liberties abuses — have begun very delicately to raise doubts and concerns about the committee's actions.

But the most serious constitutional problem is not the specific investigative acts of the committee but the very existence of the committee itself. There is ample reason to doubt the constitutionality of this committee's existence.

When crimes are committed in the United States, there are two branches of government — and only two — vested by the Constitution with the power to investigate criminal suspects and adjudicate guilt: the executive branch (through the FBI and DOJ) and the judiciary. Congress has no role to play in any of that, and for good and important reasons. The Constitution places limits on what the executive branch and judiciary can do when investigating suspects and declaring citizens guilty, safeguards designed to protect fundamental rights of American citizens. No searches can be executed by the FBI without judicial approval in the form of warrants; nobody can be publicly declared guilty without a wide range of rights being guaranteed (the right of cross-examination, a jury trial of one's peers, ample due process protections, etc.); private data about citizens cannot be collected without their consent absent an array of protective procedures.

One particularly acute danger of allowing Congress to investigate private citizens — that they operate without the safeguards imposed on the FBI and other law enforcement authorities — was highlighted last month by the left-liberal legal scholar Elizabeth Goitein, a long-time civil liberties lawyer who worked with Democratic Sen. Russ Feingold (D-WI), was a trial lawyer in the DOJ, and now co-directs the Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty and National Security Program. Writing at the legal site Just Security, which became one of the most vocal critics of the Trump presidency and the Trump DOJ, Goitein sounded the alarm about the "troubling” nature of allowing Congress to assume responsibility for investigating potential crimes of 1/6 by using broad subpoenas to third-party communication carriers:

Key constitutional safeguards that protect Americans’ privacy against intrusions by the executive branch – such as the requirement to obtain a warrant — are notably absent when it comes to congressional investigations. Nor do the statutory privacy protections Congress has enacted adequately fill the gap. If we acknowledge that Congress, just like the executive branch, is capable of abusing its powers and infringing on the rights of Americans, it follows that Americans need a better way of enforcing those rights than the law currently provides.

For precisely these reasons, the U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly prohibited Congress from attempting to perform the law enforcement and criminal investigative functions reserved exclusively to the executive branch and the courts. While Congress does have the power in some circumstances to conduct investigations and issue subpoenas even aimed at private citizens, they are permitted to do so only for one of two reasons: (1) to gather information to help lawmakers write or rewrite laws, or (2) to assert oversight over executive branch agencies as part of the constitutional design of checks and balances.

There are numerous well-known examples of legitimate congressional investigations motivated by one of these two valid purposes. When Congress investigated steroid use in Major League Baseball, it did so to determine whether it should change or abolish the league's antitrust exemption that Congress had bestowed through legislation. When Congress summons Wall Street or tech executives to testify, it does so to determine whether legal modifications governing those industries are needed. When Congress investigated the Iran-Contra scandal, the deaths of U.S. personnel at Benghazi, the CIA torture program, the failures of the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the evacuation from Afghanistan, it was fulfilling its obligations to exert oversight over the executive branch agencies to ensure competence and/or compliance with the law — a central feature of checks and balances. In the case of Watergate, Bill Clinton's perjury, or Trump's various alleged transgressions, congressional investigations were based on the constitutional power of impeachment. The 9/11 Commission was devoted to one task — finding out what happened — but was constitutionally valid because it was the president and executive branch which oversaw its creation and implementation in conjunction with congressional legislation.

But what Congress cannot do is investigate private citizens to determine if they committed crimes or issue subpoenas simply to satisfy a desire "to know what happened” — exactly what the Select Committee on 1/6, by its own admission, is seeking to do. The Supreme Court has explicitly imposed this limit on congressional investigative power over and over, and has banned congressional investigations which were not geared toward either one of those two legitimate investigative purposes.

The last time the Supreme Court explained the limits on Congress’s investigative power was last year, in the case of Trump v. Mazars USA, LLP, which, in an opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts, ruled that House oversight committees had the power to obtain Trump's tax returns. The Court noted how unprecedented this dispute was, since typically such conflicts between Congress and the president over access to presidential information are resolved without judicial intervention. But in so ruling, the Court reviewed the history of the limits on congressional investigative power, particularly when it comes to private citizens, and made clear how vital and significant those limitations are (emphasis added):

Because this power [of investigation] is “justified solely as an adjunct to the legislative process,” it is subject to several limitations. Most importantly, a congressional subpoena is valid only if it is “related to, and in furtherance of, a legitimate task of the Congress.” The subpoena must serve a “valid legislative purpose,” Quinn v. United States, 349 U.S. 155, 161 (1955); it must “concern[ ] a subject on which legislation ‘could be had,’” Eastland v. United States Servicemen’s Fund, 421 U.S. 491, 506 (1975) (quoting McGrain, 273 U. S., at 177).

Furthermore, Congress may not issue a subpoena for the purpose of “law enforcement,” because “those powers are assigned under our Constitution to the Executive and the Judiciary.” Quinn, 349 U. S., at 161. Thus Congress may not use subpoenas to “try” someone “before [a] committee for any crime or wrongdoing.” McGrain, 273 U. S., at 179. Congress has no “‘general’ power to inquire into private affairs and compel disclosures,” id., at 173–174, and “there is no congressional power to expose for the sake of exposure,” Watkins, 354 U. S., at 200. “Investigations conducted solely for the personal aggrandizement of the investigators or to ‘punish’ those investigated are indefensible.” Id., at 187.

The widely respected Congressional Research Service (CRS), used by lawmakers to understand the legal limits on their power, earlier this year published a treatise on this exact question. In it, they emphasized that “as broad as the investigative power may be, it is not unlimited,” adding: "Congress does not act with a legislative purpose when investigating private conduct that has no nexus to the legislative function.” Specifically, the Constitution bars investigations that have little or no real purpose other than simply to find out what happened, no matter how consequential an event may be. In other words, the mantra that "we need to know” is a classic example of an invalid motive for a congressional investigation into the acts of private citizens. Criminal acts are to be investigated solely by the other two branches:

The Supreme Court has cautioned that because the power to investigate derives from Article I’s grant of “legislative powers,” it may be exercised only “in aid of the legislative function.” No inquiry “is an end in itself” but instead “must be related to, and in furtherance of, a legitimate task of the Congress.” The Supreme Court has generally implemented this principle by requiring that compulsory committee investigative actions—including subpoenas for documents or testimony—serve a valid legislative purpose.

The CRS report laid out the limited framework that allows Congress to act as an investigative body. For a congressional investigation to be a valid exercise of lawmaking duties, an investigative body "must be understood to include 'inquiries into the administration of existing laws, studies of proposed laws, and surveys of defects in our social, economic or political system for the purpose of enabling the Congress to remedy them.’”

Does anyone believe that the purpose of the Select Committee on 1/6 in digging up as much dirt as possible on the private citizens involved in securing 1/6 protest permits has anything remotely to do with such concerns? In what conceivable way will finding out which protesters did what in the days leading up to 1/6 help Congress amend existing laws? Their motive could not be clearer: to parade around those they consider to be bad and deplorable people, to bestow on their sadistic liberal flock the enjoyment of watching their political enemies suffer public stigma, vilification and shame, and attempt to prove what the DOJ has thus far refused even to allege: that January 6th was driven not by common crimes and misdemeanors nor a protest that organically erupted into a riot, but instead, a historically momentous, seditious, insurrectionary plot.

Supreme Court Limits on Congressional Investigations of Private Citizens

Prohibitions by the Supreme Court on Congressional attempts to investigate private citizens were first established in the 19th Century. In its 1880 ruling in Kilbourn v. Thompson, the Court invalidated a congressional investigation of a citizen they believed had defrauded the government and bankruptcy courts. When the target of their investigation refused to comply with a subpoena for the production of documents, the House sought to hold him in criminal contempt. But the entire congressional proceeding, ruled the Court, was unconstitutional because its real purpose was not to consider legislative reforms, as the House had claimed, but rather to investigate possible crimes by this citizen — a power only the executive and judicial branches have the right to exercise:

An act of Congress which proposed to adjudge a man guilty of a crime and inflict the punishment, would be conceded by all thinking men to be unauthorized by anything in the Constitution. . . . In looking to the preamble and resolution under which the committee acted, before which Kilbourn refused to testify, we are of opinion that the House of Representatives not only exceeded the limit of its own authority, but assumed a power which could only be properly exercised by another branch of the government, because it was in its nature clearly judicial. . . .

We are of opinion, for these reasons, that the resolution of the House of Representatives authorizing the investigation was in excess of the power conferred on that body by the Constitution; that the committee, therefore, had no lawful authority to require Kilbourn to testify as a witness beyond what he voluntarily chose to tell; that the orders and resolutions of the House, and the warrant of the speaker, under which Kilbourn was imprisoned, are, in like manner, void for want of jurisdiction in that body, and that his imprisonment was without any lawful authority.

When it comes to the 1/6 Committee, there is not even a pretense that their investigation of dozens if not hundreds of private citizens is designed to aid them in enacting new laws or rewriting existing ones. All of the acts in which they believe their investigative targets engaged — conspiracy to incite insurrection, to interfere in democratic processes, attempts to kill or kidnap elected officials — are all already crimes: quite serious felonies. Even if they did intend to heighten those punishments or expand the scope of what constitutes criminal “insurrection,” or even if they are considering reforms to the way the Electoral College vote is certified, there is no conceivable argument that invading the private data of 1/6 protesters or those suspected of supporting the underlying political cause of protesting the 2020 election outcome could help in reforming congressional statutes.

One could conceive of legitimate areas of inquiry that would render the Select 1/6 Committee valid under the U.S. constitutional framework. If, for instance, they were attempting to understand mistakes made by the Capitol Police, or why the FBI failed to apprehend the nature of the threat, or, much more interestingly, what role FBI agents and informants played in the events themselves, there would be no question that this would be a valid exercise of congressional investigative power, since their targets would be the government agencies over which they have oversight responsibilities. But the committee exhibits little to no interest in any of those questions. (Congress also has the power to investigate suspected wrongdoing by members of the Senate or House, but such investigations are required to be conducted exclusively through the Ethics Committee, which provides a range of protections, such as an equal number of members of each party, that standard committees do not).

Indeed, in unguarded moments, leading members of the 1/6 Committee have touted the real purpose of their investigation in exactly the terms the Court has repeatedly held were the hallmark of invalid probes. They rarely, if ever, pretend that the purpose of these invasive probes or the committee itself is to aid in the process of new legislation — what viable case could they even make for that? Nor do they offer any pretense of “oversight”: only a tiny fraction of their work is even remotely related to the conduct of executive branch agencies or suspected involvement by Trump officials in the events of 1/6. When justifying the creation of the 1/6 Committee and its invasive actions, they simply assert that they must know what took place surrounding such an important event, or that they need to determine who committed what crimes. That, as the CRS report made clear, is the classic improper inquiry: “No inquiry 'is an end in itself.'”

In a joint statement on September 16, Chairman Bennie Thompson (D-MS) and his Vice Chair, Liz Cheney (R-WY), made clear that they simply want to know what happened: “the Select Committee is dedicated to telling the complete story of the unprecedented and extraordinary events of January 6th, including all steps that led to what happened that day.” Trump impeachment star Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD), now a Select Committee member, sounded like a sheriff as he touted the committee's law enforcement goals to CNN: “You know it's an overwhelming task because we're talking about one of the largest crimes in American history, involving thousands of people and thousands of potential offenses.” Thompson was explicit about their "just-need-to-know” curiosity: "We have to see from the standpoint of who helped finance what went on. We have to see what individuals had something to do with getting people here. We have to see who, in effect, pushed out misinformation and how social media was a part of that effort." What gives Congress the right to investigate which citizens promoted a protest on social media?

Liz Cheney explained the committee's goal this way: “We're telling the American people the story of what happened,” adding: “We're very focused on every aspect that we've laid out. What happened in the run-up to January 6, what happened on the 6th. What happened after the 6th." This left CNN, obviously sympathetic to the Democrats who pushed for the investigation, to acknowledge the utter lack of clarity regarding the committee's motives: “Members of the select committee tasked with examining the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol met behind closed doors with their staff for more than five hours on Monday night -- but as they seek thousands of documents and hours of potential interviews, the ultimate course of the ambitious investigation is still not clear."

The only reference to the possibility of legal reform that appears in the enabling resolution creating the committee — which enumerates the ostensible purposes and functions of the investigation — is the claim that it seeks to evaluate “the structure, authorities, training, manpower utilization, equipment, operational planning, and use of force policies of the United States Capitol Police.” While investigating law enforcement agencies is clearly a valid congressional function, virtually none of the subpoenas the committee has issued or the private citizens it has targeted has any conceivable relationship to questions about the procedures and failures of the Capitol Police.

Anyone who believes that Congress has the right to haul American citizens before itself for interrogation and to obtain their most private data simply to "find out what happened” is someone who recognizes no limits on Congress’s investigatory powers. They are also someone either unaware of or indifferent to the long history of jurisprudence that has made clear exactly how menacing such congressional inquiries can be, and how unconstitutional they are. The Kilbourn Court emphasized exactly this lack of legislative purpose in invalidating the congressional investigation into individuals suspected of defrauding creditors:

We think it equally clear that the power asserted is judicial and not legislative. The resolution adopted as a sequence of this preamble contains no hint of any intention of final action by Congress on the subject. In all the argument of the case no suggestion has been made of what the House of Representatives or the Congress could have done in the way of remedying the wrong or securing the creditors of Jay Cooke & Co., or even the United States. Was it to be simply a fruitless investigation into the personal affairs of individuals? If so, the House of Representatives had no power or authority in the matter more than any other equal number of gentlemen interested for the government of their country. By 'fruitless' we mean that it could result in no valid legislation on the subject to which the inquiry referred.

While the Court in the 20th Century has loosened some of the more extreme limits imposed on congressional investigative power by the ruling in Kilbourn, that "loosening” has been applied to the right of Congress to interrogate executive branch officials. When it comes to Congressional probes into the acts of private citizens, the Court continues to impose strict limitations. In its 1962 ruling in Hutchinson v. U.S., often cited as an attempt by the Court to broaden congressional power, the Court approved the Congressional inquiry before it regarding abuses by labor leaders solely because the investigation was limited to understanding how labor laws should be revised:

The information sought to be elicited by the Committee was pertinent to the legislative inquiry. The Committee was investigating whether and how union funds had been misused, in the interest of devising a legislative scheme to deal with irregular practices….The Committee's interrogation was within the express terms of its authorizing resolution. If the Committee was to be at all effective in bringing to Congress' attention certain practices in the labor-management field which should be subject to federal prohibitions, it necessarily had to ask some witnesses questions which, if truthfully answered, might place them in jeopardy of state prosecution.

And even with the erosion of the Kilbourn limits, the Hutchinson court nonetheless recognized that its key proposition — the one most relevant to questions about the 1/6 Committee — remains fully valid: “Kilbourn is authority for the proposition that Congress cannot constitutionally inquire 'into the private affairs of individuals who hold no office under the government' when the investigation 'could result in no valid legislation on the subject to which the inquiry referred.'” As the CRS described the evolution of this case law: “the Court appears to have made a distinction between investigating purely private conduct of private citizens, which typically would not serve a legislative purpose, and investigating the private conduct of public office holders, which may, in some circumstances, serve a legislative purpose due to Congress’s role in preserving good government."

Indeed, in Hutchinson, Justice Brennan wrote a separate opinion to make clear that the Congressional investigation before it was valid only because “the Select Committee was seeking factual material to aid in the drafting and adopting of remedial legislation to curb misuse by union officials of union funds,” and “that the Committee's interrogation of the petitioner about the use of union funds to forestall that indictment did not stray beyond the range of the Committee's valid legislative purpose.”

In perhaps the most relevant section of the 2021 CRS report, the authors emphasized that what makes a Congressional investigation particularly dubious and dangerous is when the genuine and clear goal is to prove that particular individuals committed crimes and to expose them to public vilification or other forms of societal sanctions:

A second class of investigations that may lack a legislative purpose are those that appear to usurp functions exclusively committed to another branch of government. In Barenblatt v. United States the Supreme Court explained, “Lacking the judicial power given to the Judiciary, [Congress] cannot inquire into matters that are exclusively the concern of the Judiciary. Neither can it supplant the Executive in what exclusively belongs to the Executive.” The Court elaborated on this separation of powers line of reasoning in Watkins, where it stated that Congress is not “a law enforcement or trial agency. These are functions of the executive and judicial departments of government.… Investigations conducted solely for the personal aggrandizement of the investigators or to ‘punish’ those investigated are indefensible.” Most recently, in Mazars, the Court reaffirmed that Congress may not issue a subpoena for the purpose of “law enforcement,” because “those powers are assigned under our Constitution to the Executive and the Judiciary.” Thus Congress may not use subpoenas to “try” someone “before [a] committee for any crime or wrongdoing.”

There is, as noted, little tolerance with certain elite political and media sectors for constitutional and legal objections to U.S. responses to 1/6 given how traumatizing and evil they believe 1/6 to be. But these limits on congressional power to investigate private citizens are not mere annoying legalisms but vital safeguards against the repetition of some of the worst abuses of civil liberties in U.S. history.

Indeed, it is not a coincidence that several of the key Supreme Court precedents imposing limits on congressional investigatory power were from the McCarthy era. Those judicial rebukes were provoked when multiple committees were attempting to haul private citizens before Congress for interrogation about their political activities and associations in the name of combating what they claimed was a menacing domestic ideological threat whose aim was the overthrow of the U.S. Government: precisely the rationale offered by Democrats and their Cheney/Kinzinger allies now to justify their similar probes into American citizens.

The McCarthy Era and Emergence of Left-Liberal Objections

The perils and abuses of the 1/6 Committee have become so glaring and extreme that some important voices on the liberal-left are finally beginning to raise concerns. When doing so, they are notably invoking the specter of the McCarthy hearings.

Earlier this month, The Project On Government Oversight (POGO), devoted to combating government corruption and abuse of power, sent a letter to Chairman Thompson and Vice Chair Cheney, urging them to exercise “care in your committee’s use of subpoena authority to collect private communications and other information.” The group warned that any probe must “be limited to furthering the committee’s legislative purposes, including introducing new laws to prevent another attack on the U.S. Capitol.” The group is particularly concerned about subpoenas that “relate to conduct that is protected as free speech and association, and private information that is protected by the Fourth Amendment.” And they invoked past abuses, including the McCarthy hearings, as a pointed warning about the dangers of the subpoenas issued by the 1/6 Committee:

Past Congressional actions — especially those justified in the name of security — show the importance of exercising such care. Most infamously, during the Red Scare of the 1940s and 1950s, Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee both used congressional powers to collect private information on, expose, and demonize communist sympathizers. In 2011, the House Committee on Homeland Security led hearings focused on targeting and disparaging Muslim communities, a measure Chairman Thompson rightfully criticized at the time in his role as the committee’s ranking member.

To identify the specific civil liberties abuses starting to emerge, POGO wrote, in language designed to appeal to the political sensibilities of liberals: “While claims of election fraud were baseless and have seriously undermined public faith in our democracy, false and grossly offensive speech is still constitutionally protected. Accordingly, we urge the committee to be especially cautious in its demands for records that could implicate First Amendment rights or set precedent for future demands that chill First Amendment-protected activities.”

Even more emphatic concerns about the Committee's work were raised by Goitein, currently the co-director of the Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty and National Security Program. In the above-referenced article at the anti-Trump Just Security site, Goitein warned of how dangerous these latest third-party subpoenas issued by the 1/6 Committee are. And she, too, compared them to some of the worst abuses of the McCarthy hearings:

Although those lists [of people targeted by third-party subpoenas] have not been released publicly, the letters describe some of the categories into which the people fall—for instance, “individuals who were listed on permit applications or were otherwise involved in organizing, funding, or speaking at the January 5, 2021, or January 6, 2021, rallies in the District of Columbia relating to objecting to the certification of the electoral college votes.”

In other words, the requests aren’t limited to people who participated in the attack on the Capitol; they sweep in those who were lawfully exercising their right to protest. . . .

Past Congressional actions — especially those justified in the name of security — show the importance of exercising such care. Most infamously, during the Red Scare of the 1940s and 1950s, Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee both used congressional powers to collect private information on, expose, and demonize communist sympathizers.

As noted above, Goitein documented that one reason it is so important to limit Congressional investigatory activities is that Congress operates without many of the safeguards that govern the FBI's ability to obtain information on Americans. And she makes clear that the intrusive and extraordinary third-party subpoenas issued by the 1/6 Committee seek exactly the type of information that the FBI would be barred from obtaining without judicial approval:

The committee asked the companies to preserve data of all kinds, including emails, text messages, voice mail messages, location information, and call data records. The requests thus encompass not only non-content information, sometimes known as “metadata,” but also communications content, which ordinarily receives the highest level of constitutional and statutory protection. The requests also include cell site location information, which law enforcement officers must get a warrant to obtain under the Supreme Court’s 2018 decision in Carpenter v. United States….

A rule that allows Congress unfettered access to the emails, text messages, and geolocation information of protest organizers will serve none of us well in the long run.

So many of these controversies were, or at least should have been, resolved when the Supreme Court twice intervened in the congressional hearings during the McCarthy era to conclude that Congress was exceeding its authority in its targeting of private citizens. There are some who believe that the domestic threat of communism which the McCarthyite committees cited was more dangerous than the ideology that drove 1/6, while others believe the opposite. But those debates are completely irrelevant to the legal principles governing limitations on congressional investigative authorities; these limitations do not change based on how grave the threat one believes Congress is confronting.

Indeed, the argument made by Congress in the 1950s to justify its investigations into private citizens is strikingly similar to the one advocates of the 1/6 Committee offer now. As the Supreme Court summarized that rationale in its 1957 ruling in Watkins v. U.S.: “The Government contends that the public interest at the core of the investigations of the House Un-American Activities Committee is the need by the Congress to be informed of efforts to overthrow the Government by force and violence, so that adequate legislative safeguards can be erected.” But in both of the McCarthy era cases decided by the Supreme Court, that rationale was rejected as an invalid basis for Congress's investigative tactics.

In 1955, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the criminal convictions for contempt of Congress for two U.S. citizens who were summoned to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). The two union members at issue in the case, Quinn v. U.S., refused to answer questions about whether they had ever been a member of the Communist Party, insisting such questions violated their First Amendment rights of speech and association and that Congress was exceeding its powers to investigate private citizens.

The Court, though recognizing the validity of congressional investigations in some circumstances, quickly noted that the power is not absolute and concluded, despite Congress’ claim to be facing an existential insurrectionary movement, that they were exceeding their powers: "the power to investigate must not be confused with any of the powers of law enforcement; those powers are assigned under our Constitution to the Executive and the Judiciary."

Two years later, the Supreme Court again intervened in the congressional investigations regarding plots of domestic communist insurrection to impose further limits on Congress’s investigatory power. In Watkins v. U.S., the Court ruled unconstitutional congressional attempts to target another union member summoned to appear before the HUAC. The union member explicitly refused to answer any questions about his associations with other citizens who were members of the Communist Party in the past, telling the committee: "I do not believe that such questions are relevant to the work of this committee, nor do I believe that this committee has the right to undertake the public exposure of persons because of their past activities.” He was convicted of criminal contempt of Congress after the committee referred him to the DOJ for prosecution.

As it did two years earlier in Quinn, the Supreme Court court recognized that congressional power to investigate is "broad,” and “encompasses inquiries concerning the administration of existing laws, as well as proposed or possibly needed statutes.” And it “it comprehends probes into departments of the Federal Government to expose corruption, inefficiency or waste.” Beyond that, however, Congress has no power to investigate private citizens, and transgressions of this power become particularly toxic when they seek to expose a citizens’ political beliefs and associations:

But, broad as is this power of inquiry, it is not unlimited. There is no general authority to expose the private affairs of individuals without justification in terms of the functions of the Congress. This was freely conceded by the Solicitor General in his argument of this case. Nor is the Congress a law enforcement or trial agency. These are functions of the executive and judicial departments of government. No inquiry is an end in itself; it must be related to, and in furtherance of, a legitimate task of the Congress. Investigations conducted solely for the personal aggrandizement of the investigators or to "punish" those investigated are indefensible. . . .

Abuses of the investigative process may imperceptibly lead to abridgment of protected freedoms. The mere summoning of a witness and compelling him to testify, against his will, about his beliefs, expressions or associations is a measure of governmental interference. And when those forced revelations concern matters that are unorthodox, unpopular, or even hateful to the general public, the reaction in the life of the witness may be disastrous. . . . Nor does the witness alone suffer the consequences. Those who are identified by witnesses, and thereby placed in the same glare of publicity, are equally subject to public stigma, scorn and obloquy. Beyond that, there is the more subtle and immeasurable effect upon those who tend to adhere to the most orthodox and uncontroversial views and associations in order to avoid a similar fate at some future time. That this impact is partly the result of nongovernmental activity by private persons cannot relieve the investigators of their responsibility for initiating the reaction.

The Supreme Court in these McCarthy-era cases was aware of the possibility that Congress would concoct a legislative pretext to justify what was intended to be a punitive investigation. For that reason, the Watkins court explained "that the mere semblance of legislative purpose would not justify an inquiry in the face of the Bill of Rights.” In other words, the more invasive the investigation of private citizens — the more their political beliefs and associations are to be exposed to the world — the greater the burden imposed on Congress to demonstrate a clear nexus between their investigation and a valid lawmaking purpose. Simply because Congress claims that they are conducting an investigation of private citizens in order to reform a law or to exercise oversight does not magically transform the investigation into a valid one:

The critical element is the existence of, and the weight to be ascribed to, the interest of the Congress in demanding disclosures from an unwilling witness. We cannot simply assume, however, that every congressional investigation is justified by a public need that overbalances any private rights affected. To do so would be to abdicate the responsibility placed by the Constitution upon the judiciary to insure that the Congress does not unjustifiably encroach upon an individual's right to privacy nor abridge his liberty of speech, press, religion or assembly. . . .

In deciding what to do with the power that has been conferred upon them, members of the Committee may act pursuant to motives that seem to them to be the highest. Their decisions, nevertheless, can lead to ruthless exposure of private lives in order to gather data that is neither desired by the Congress nor useful to it.

Just as was true of 9/11, the mere invocation of 1/6 and emotionally-packed words such as “attack” and "terrorists” should not provoke reflexive support for whatever is done in its name. Whenever Congress starts investigating private citizens, serious questions regarding constitutionality and civil liberties are automatically raised. That is even more true when the basis of investigation, as is true of the 1/6 Committee, is the political beliefs, associations and protest activities of those citizens.

Feeding the Flock: The Real Reason for the 1/6 Committee

Underlying so much of the anger and resentment surrounding 1/6 is the complete dissonance between the narrative fed to the citizenry by Democrats and their media allies on the one hand, and the legal realities on the other. It must be infuriating and baffling to a large sector of the population to have been convinced that what happened on January 6 was an unprecedentedly dangerous insurrection perpetrated by an organized group of seditious traitors who had plotted to kidnap and murder elected officials, only for the Biden DOJ to have charged exactly nobody with any criminal charges remotely suggesting any of those melodramatic claims.

This was the same frustration and confusion that beset a large portion of liberal America when they were led to believe for years that Robert Mueller was coming to arrest all of their political enemies for treason and criminal conspiracy with Russia, only for the FBI Superman to close his investigation without charging a single American with criminal conspiracy with Russia and then issuing a report admitting that he could not find evidence to establish any such crime. How to keep the flock loyal when the doomsday prophecies continue to be unfulfilled, as the World-Ending Date comes and goes without so much as a bang, let alone an explosion?

Adam Schiff's new book — which essentially claims that Mueller is senile and was suffering from pitiful dementia — is obviously intended to provide some solace or at least a framework of understanding for disappointed liberals to keep the faith, but deep down, they know what they were expecting. The endorphin-producing fantasies on which they fed for years — of Trump and Trump, Jr. and Jared and Bannon and Ivanka being frog-marched out of the White House by armed, strapping FBI agents — were way too viscerally arousing for them to simply forget that none of it happened.

A repeat of this disorientation and disillusionment when it comes to 1/6 could be quite dangerous for Democrats. It could be devastating to the media outlets which survive on serving the Democrats’ messaging and feeding dramatic conspiracy theories to the beleaguered liberal flock. In the days and weeks following 1/6, liberals really thought that dozens of members of Congress — from Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz to Matt Gaetz and Marjorie Taylor Greene — would be not just expelled from Congress but summarily imprisoned as traitors by a newly righteous Justice Department. They were led to believe that, with Bill Barr out of the way, Trump and his mafia family would finally pay for their crimes. Instead, they have been served a tepid, cautious, and compartmentally conservative Merrick Garland who seems barely able to send the Evil Insurrectionists — many of whom are just hapless and impoverished lost souls — to prison for more than a few months. The harsh reality is yet again destroying their cravings for promised vengeance and retribution, and something must be done, lest the cult loyalty be lost forever.

That is, at bottom, what the 1/6 Committee is really for. The House Democrats have smart lawyers who are fully aware of all the above-discussed case law and other limitations on congressional power. That is why they purposely structured their third-party subpoenas to ensure nobody can challenge them in court: they know those subpoenas vastly exceed the limits of their authority and cannot withstand judicial scrutiny.

This congressional committee is designed to be cathartic theater for liberals, and a political drama for the rest of the country. They know Republicans will object to their deliberately unconstitutional inquisitions, and they intend to exploit those objections to darkly insinuate to the country that Republicans are driven by a desire to protect the violent traitors so that they can deploy them as an insurrectionary army for future coups. They have staffed the committee with their most flamboyant and dishonest drama queens, knowing that Adam Schiff will spend most of his days on CNN with Chris Cuomo comparing 1/6 to Pearl Harbor and the Holocaust; Liz Cheney will equate Republicans with Al Qaeda and the Capitol riot to the destruction of the World Trade Center; and Adam Kinzinger will cry on cue as he reminds everyone over and over that he served in the U.S. military only to find himself distraught and traumatized that the real terrorists are not those he was sent to fight overseas but those at home, in his own party.

But the manipulative political design of this spectacle should not obscure how threatening it nonetheless is to core civil liberties. Democrats in politics and media have whipped themselves into such a manic frenzy ever since 1/6 — indeed, they have been doing little else ever since Trump descended the Trump Tower escalator in 2015 — that they have become the worst kinds of fanatics: the ones who really believe their own lies. Many genuinely believe that they are on the front lines of an epic historical battle against the New Hitler (Trump) and his band of deplorable fascist followers bent on a coup against the democratic order. In their cable-and-Twitter-stimulated imaginations, shortly following this right-wing coup will be the installation of every crypto-fascist bell and whistle from concentration camps for racial and ethnic minorities to death or prison for courageous #Resistance dissidents. At some point, the line between actually believing this and being paid to pretend to believe it, or feeling coerced by cultural and friendship circles to feign belief in it, erodes, fostering actual collective conviction and mania.

And when fanatics convince themselves that their cause is not only indisputably just but an imperative for survival, then any doubts or questions about methods and weapons can no longer be acknowledged. The war they are fighting is of such overarching importance and righteousness that there is no such thing as unjust or excessive means to achieve it. Just a cursory examination of liberal discourse is enough to see that they have long ago arrived at and flew past this point of sectarian zealotry. And that is what explains their overwhelming support for state and corporate censorship of the internet, increasing reverence for security state agencies such as the CIA and FBI, love for and trust in corporate media, and a belief that no punishment or level of suffering is excessive when it comes to retaliation against their political enemies, including but not only those who participated in any way in the 1/6 protests.

This is, after all, a movement that has long opposed the death penalty and whose more left-wing factions spent 2020 rioting in cities to protest police violence and chanting "Defund the Police!" yet their only lament about Ashli Babbitt seems to be that she was the only pro-Trump "fascist" shot and killed by noble police officers on that day. They have pranced around for decades as criminal justice reformists, denouncing harsh prosecutorial strategies and judicial punishments, yet are indignant that people who put their feet on Nancy Pelosi's sacred desk or vandalized the sacred halls of American power with their dirty and deplorable presence are not spending decades in a cage. They spent 2020 depicting police officers as racist savages, only to valorize the Capitol Police as benevolent public servants whom only barbarians would want to harm, then gave them an additional $2 billion to intensify their surveillance capabilities and augment their stockpile of weapons. Their fury that Trump officials did not end up spending decades in cages due to vague associations with Russians is exceeded only by their rage that pro-Trump protesters at the Capitol are being sentenced to months rather than years or decades in prison.

A political movement that operates from the premise that its cause is too important to be constrained is one that inevitably becomes authoritarian. That such authoritarianism is the defining feature of American liberalism has been evident for several years. And an investigative congressional committee that they control, aimed squarely at their political enemies, accompanied by demands that anyone resisting it be imprisoned, can only lead to very dark and dangerous destinations.

To support the independent journalism we are doing here, please obtain a gift subscription for others and/or share the article:

This is a spectacularly brilliant political and legal analysis. I assumed Glenn's silence the last week or so meant he was working on something big, but this is far beyond anything I could have imagined. This is the finest writing and analysis I have seen in my 64 years. Glenn is a genius. A national treasure. A freedom fighter.

This is so extraordinary that I found myself pausing after every sentence to contemplate and savor. It is encyclopedic and irrefutable.

The power in Glenn Greenwald's mind and writing is incredible. We could even say that this bombshell is of nuclear magnitude.

This one article is worth the price of a year’s subscription. I don’t have anything to say but thank you - I’m still digesting and dealing with my feelings after finishing it.